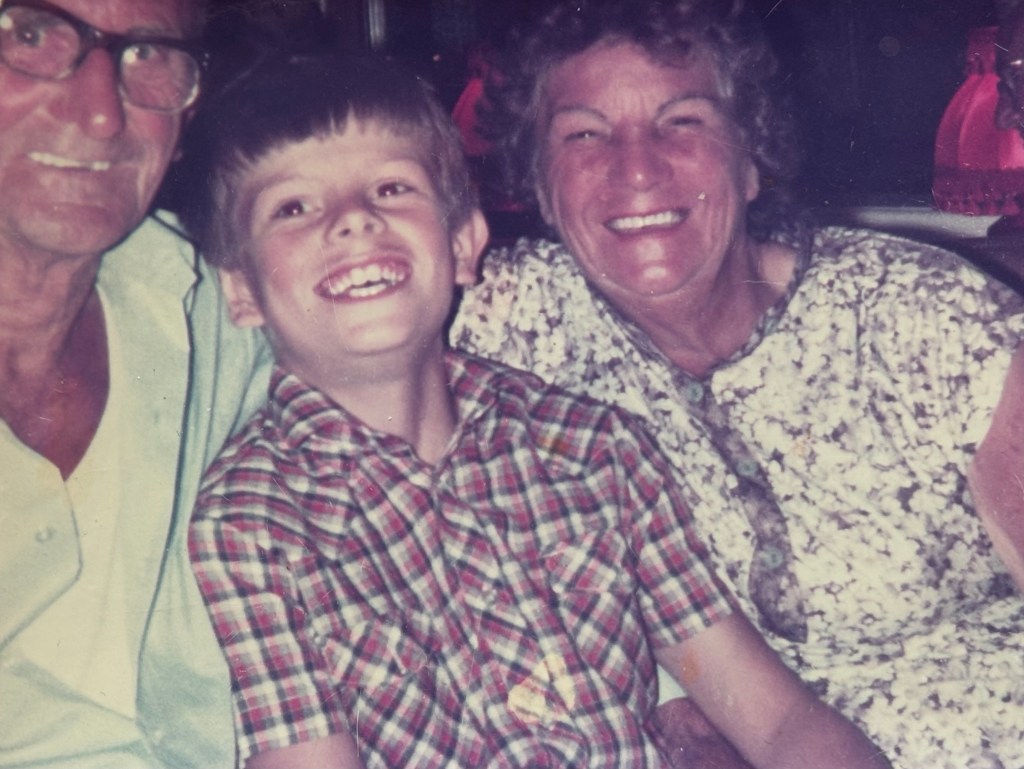

I was very close to my grandparents as I was growing up.

They lived just seven doors away from me and I was round their house all the time.

The town where we lived at the northern edge of Manchester was dominated by a huge, red giant — The Warwick Mill.

Nan, a mill girl, worked in The Warwick for many years. Pop, my granddad, ran the trucks at the cables factory up the road.

Although the mill towered over us, I rarely noticed it as a boy apart from when I waited with my mum for Nan to clock out after one of her last shifts.

Nan worked in the rag trade then — inspecting the baby clothes that were made there by a small army of women machinists.

That can’t have been long before The Warwick closed its doors – the cotton industry already gone.

But I found out recently using census returns that Nan’s brothers were spinners at the mill too when Lancashire thread was king in the 1920s.

Liver and onions

The Warwick dominated our lives beyond the evening shadows it cast over us — even influencing the way Nan cooked.

You might not know this but in Manchester and south Lancashire we always call the midday meal dinner.

The evening meal is known to us as tea.

It’s a relic of the days when the workers were forced by the beat of the mill engines to have their main hot meal in the early afternoon.

When they got home shattered from the backbreaking work they only had the time and energy to make a light snack.

“In Manchester everybody, master and man, dines at one o’clock,” a journalist named Angus Reach wrote of the newly industrialised town way back in 1849.

“Streets and lanes, five minutes before lonely and deserted, are echoing the trampling of hundreds of busy feet.”

Even after she retired, Nan stuck to this tradition — cooking up a hot dinner at midday and making a sandwich or “butty” for our tea.

Dinner cooked by Nan for Pop and me each morning meant liver and onions, or “tater ash” — a thin liquor of beef, potatoes, carrots, an onion and an Oxo cube or two.

Often she added a crust of pastry to make a homemade pie — still one of my favourite meals today.

Sometimes, Nan’s ash (the h of hash was never pronounced) also included chunks of kidney, or jelly-like globs that I would spoon carefully to the side of the plate.

“That’ll stick to your ribs,” she would say, encouraging me to gulp the globs down for my own good. I later discovered it was cow heel.

Sometimes at Nan’s house, I’d only head back home after a teatime tongue sandwich washed down with a glass of “sterra” — sterilised milk.

It must have been good for us as I was as fit as a butcher’s dog growing up and Nan and Pop lived into their 80s.

The Wakes

The mill impacted our holidays too – due to the old tradition of The Wakes.

Starting in the nineteenth century, the mills in Lancashire would shut for one week in the summer for maintenance and repairs.

To keep up production, each town closed all its mills and sent the workers on holiday on a different week from the neighbouring towns.

The town’s entire workforce would then decamp to Blackpool on the Lancashire coast, with workers from the next town arriving the following week.

Even though the tradition was dying in the 1980s, as package holidays abroad were becoming popular, Nan and Pop took me to the same seafront boarding house at the seaside resort for our Wakes in the summer.

She knew almost all of the people on the old Yelloway’s coach as we climbed into our dusty seats at our town’s bus station.

When I got married, I moved back to my home town.

The Warwick Mill is still here, towering over a new supermarket.

The mill has long been empty now — the windows are all smashed and plants are growing out of the roof.

Nan and Pop are gone too.

They died within a year of each other at the end of the 1990s.

They both played such a big part in making me the person I am today.

Most of all I miss Nan’s strong mill worker’s arms she would wrap around me, her laughter, her stories and the unbeatable taste of her homemade hash.

There are so many things I wish I had asked her while I was growing up.

But every time I walk past the giant red mill with the broken windows, it reminds me of her.

Let me help you tell your story

Do you have a loved one you want to remember? Perhaps there are questions you also wished you’d asked them years ago? Let me help you to tell your family story and keep their memory alive by contacting me using the form below. Please note I do not research living people.